The “California City” podcast, and what I saw in 2005

A few weeks ago, a friend texted me a link to a podcast called “California City” that came up as a suggestion for him in his podcast app. Was this the same California City, he asked, that I had visited and reported on, had breathlessly told him about? Of course, it was.

A few weeks ago, a friend texted me a link to a podcast called “California City” that came up as a suggestion for him in his podcast app. Was this the same California City, he asked, that I had visited and reported on, had breathlessly told him about? Of course, it was.

I was an intern reporter at the Bakersfield Californian for one burning hot summer, in 2005. I’d bought a college friend’s old car for $700 to take the job. Late in the summer, I had a lead on a few stories out in Cal City. Once I saw what was happening with land sales in the town’s so-called “second community,” I started working weekends driving around the Los Angeles basin seeking to find and interview the people who had bought into the Cal City dream.

So I immediately moved the podcast, by KPCC reporter Emily Guerin, to the top of my list. The story is about a thinly populated city in the Mojave desert, California City, that has been the center of controversial land deals for more than 50 years. Hucksters have sold near-worthless desert land to outsiders, from all over the world—but especially from Los Angeles—at vastly inflated prices.

The podcast, which broadcast its 5th episode this week, has truly been a blast from the past for me. Some of the business tactics and the players have changed, but it’s amazing how much of the California City sales pitch described by Guerin’s reporting remains the same. At a dusty, sad resort called Silver Saddle Ranch & Club, a group of wealthy salespeople use high-pressure tactics to sell useless land to immigrants.

Guerin’s fantastic podcast and delves deeply into the history of California City, far beyond what I had the capacity to do 15 years ago. I’m sure her work will become the reporting of record on this topic for years to come. As Guerin’s work may now draw more attention to California City and its history, it has also inspired me to re-publish my long-lost articles in the interest of drawing an even more complete historical record.

I’ll have more to say about my impressions of the California City podcast in a future post. For now, I’ve transcribed my front-page article—The Bakersfield California’s A1 spread on Sunday, October 2, 2005. I’ll put up the sidebar piece from page A8 as a separate post once I get a chance transcribe it.

Exploiting dreams for big profits

Immigrants being sold desert land at exorbitant prices

Seda Shadkamyan, an Armenian immigrant living in Glendale, hoped that buying vacant land in the remote deserts of Kern County would give her something she could pass on to her three children. She can’t afford a house, but wanted to leave her family something of value.

But records in the Kern County Assessor’s office show she paid the seller, Silver Saddle Ranch and Club, almost 20 times the fair market value of the land.

“I feel used,” said Shadkamyan, after seeing the sales history of the land she bought for $39,500 in April. My husband didn’t want it, but I forced him,” she said. “It was my mistake.”

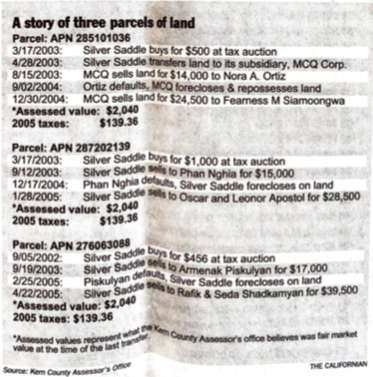

Silver Saddle sells hundreds of properties in California City each year, making millions by selling land for 10, 20, or even 50 times what the assessor’s office considers “fair market value.” While the assessor usually accepts the sales price [of a normal property] as market value, when the price seems unusually high or low, they must re-assess the property.

A second company, National Recreational Properties Inc., which uses actor Erik Estrada as its television pitch man, has sold hundreds of properties in more central areas of town for more than 10 times the fair market value, records show.

Many plots in California City have been sold, defaulted, or foreclosed on, and re-sold, ever since they were mapped out almost 40 years ago.

Looking at comparable sales in the area, the county assessor determined the fair market value of Shadkamyan’s land was $2,040. Now she’s locked into a contract under which she’ll ultimately pay, with interest, almost $50,000.

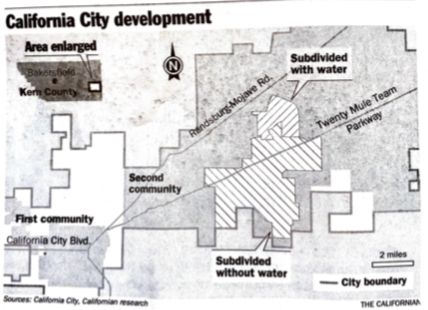

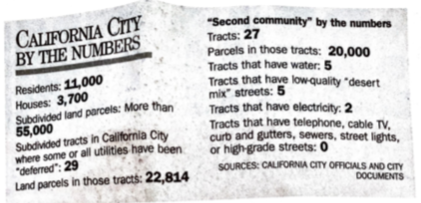

Shadkamyan’s slice of America—tract 3070, in California City—is a patch of dirt that’s tough to love. The flags that marked out her property on sales day are long gone. Her quarter-acre of desert is surrounded by about 20,000 other parcels, most of them—like hers—strips of shrub and sand without water, electricity, or paved roads.

It’s California City’s “second community,” a town that exists on paper alone. It was subdivided and zoned in the mid-1960s, along with the rest of the city. Not enough money was set aside to build utilities here, and city officials say that there are no plans to do so anytime soon. The area is about 10 miles away from California City proper, which itself is a stark and remote desert town of 11,000. The nearest shopping malls and movie theaters are in Landcaster, 40 miles to the south.

Straight Up

Silver Saddle sales manager Robert Kvassay said his company’s sales practices are straight up. He’s licensed, regulated, and careful about what his salespeople say—no one is allowed to use the word “investment” when selling, for example.

Under the company’s sales strategy, which is legal, it buys tax-defaulted land cheaply at online county auctions. Typically, small parcels with no utilities in California City’s second community sell in the low $3,000s at auction. Then the company sells the plots, mostly to out-of-county residents, sometimes for over $50,000, according to records in the Kern County Assessor’s office.

Kvassay said his sales represent the true value of the plots. He knows the dusty lots in the second community like the back of his hand. His company has been selling them—sometimes the same plot several times—for years. “That’s the market,” he said.

Differing Values

Over time, assessed value can become much lower than fair market value in California because of Proposition 13 protections against tax increases.

But at the time of transfer, in most real estate transactions, the sale price is recorded as the assessed value as well. Yet, assessor’s officials say they must record values that represent “fair market value” according to California law, and by their standards, prices commanded by companies like Silver Saddle and NRPI are far above that value.

Assessor’s officials say the buyers simply don’t know what they’re purchasing. According to California law, both parties in a transaction must be knowledgeable about the uses of land for the sales price to be considered “fair market value.”

When assessor’s officials suspect both parties aren’t knowledgeable, they assess property at what they see as the true market value.

“We have to use our judgment as to whether they seem knowledgeable or not,” Assistant Assessor Tony Ansolabehere said of people who buy lots from Silver Saddle. “To us, they don’t seem knowledgeable about that market and about those lots. Very often they’re confused about the utility situation.”

Part of the problem, he said, is that these buyers don’t have independent Realtors, appraisers and inspectors helping ensure they’re getting a good deal as in most real estate transactions.

Ansolabehere said his office can compare Silver Saddle’s prices to thousands of similar transactions, and thus know when the price is far above the market value.

In fact, some buyers find out what the county believes their land is truly worth when they get their property tax bill, Ansolabehere said. Sometimes they call the assessor’s office wondering why the listed value is so low. Most people don’t call, he said, perhaps thinking somebody made a mistake and they don’t want to do anything that sticks them with a higher tax bill.

There is a difference between what’s happening in California City and an overheated housing market such as Bakersfield, where recent studies have said homes are more than 40 percent overvalued. That difference, he said, is that similar properties in Cal City simply aren’t selling for the high prices being commanded by Silver Saddle and NRPI.

The Pitch

On the wall of Silver Saddle’s sales office about 12 miles out side of Cal City, photographs of Los Angeles neighborhoods as vacant desert lots are placed above pictures of the metropolis that exists today. “That is the great American story,” said Kvassay. “That is how cities get built.”

On the wall of Silver Saddle’s sales office about 12 miles out side of Cal City, photographs of Los Angeles neighborhoods as vacant desert lots are placed above pictures of the metropolis that exists today. “That is the great American story,” said Kvassay. “That is how cities get built.”

Near the Silver Saddle resort, a few electrified tracts sport about a dozen houses.

Those are the houses, customers and visitors said, that Silver Saddle points out before taking them to a more distant tract to sell, often on land with no utilities.

Silver Saddle finances its own sales. With a minimum 20 percent down payment, a buyer can take out a loan from the company with an interest rate of 13.9 percent.

With all land purchases, the company includes a $35 per month membership, which can be canceled, to its “private club.” Membership entails discounts on lodging and discounts up to $25 on certain amenities, such as horseback rides.

Silver Saddle would not allow a reporter to attend a land tour or be present at any negotiations. The company would also not allow any interviews of sales agents or customers at the ranch. But interviews with customers outside the ranch sketch out a similar sales pitch.

Silver Saddle has a marketing system that reaches deep into Southern California’s immigrant neighborhoods. Customers from throughout Los Angeles basin reported hearing about the company from Korean newspapers, Tagalog and Mandarin-speaking callers offering prizes, and pitches on Armenian-language television. Bonuses start at $400 for customers that refer others who buy.

The company won’t discuss any of its marketing tactics, and denies that any “cold calls,” or telemarketing takes place. The company offers free weekend trips to the ranch. Some visitors, usually those brought by friends, know there will be an attempt to sell land. Others don’t find out about the pitch until after they arrive.

After breakfast, the overnighters are taken on land tours. Customers who attended land tours say Silver Saddle sales agents deliver a clear message, whatever language they speak: get in on the ground floor. Growth is coming.

Plenty of room

On the tours, salespeople show off the new development in California City, touting the Hyundai test track and new high school as evidence that the area is growing fast.

But that growth has little connection to the second community, say local Realtors, city officials and county assessors. No money was set aside for utilities out there, other than water and low-quality streets. And city officials say “spot” development, bringing water pipes to one lot, isn’t a realistic strategy for development.

California City proper, the “first community,” which was also subdivided and sold throughout the world, still has vacant lots on nearly every block and plenty of room to grow.

One California City councilman, Nick Lessenevitch, said the town’s population of about 11,000 could triple without leaving the first community’s borders. Mayor Larry Adams said while one special project, a church, is in the works, bringing utilities to most lots in the second community is a minimum of 20 years away—if ever.

Those utilities won’t arrive until the City Council gives its OK. Recommendations about developing in the remote tracts are made to the City Council by a special two-person committee. One of the committee’s two members is Jim Quiggle, a founder of Silver Saddle who left the company a few years ago. In 2001, he sold several hundred low-value second community parcels to the company for just over $64 million. Quiggle wouldn’t comment for this report.

Bust and Boom

The land business is booming at the ranch.

The land business is booming at the ranch.

“I’m a millionaire,” said Kvassay, who has been at the company for almost 20 years. “A lot of the guys here are,” he added, gesturing to a conference room that an hour earlier was filled with customers, mostly Asian, negotiating with Silver Saddle salespeople.

In his desk drawer, Kvassay keeps a picture of himself pitching land at a seminar in South Korea. “I’ve sent agents to the Phillipines,” he said. The company’s promotional DVD can be played in seven languages.

Kvassay’s former co-worker, Jose Herrera, made his money selling the dream of development, too, and he believed in it. He even sold Silver Saddle land to the woman who later became his wife. But by the early ‘90s, Herrera saw that the second community wasn’t flourishing, despite the ranch and club that Silver Saddle had built.

“It’s a dead horse,” said Herrera.

Herrera left the company in 1992, when upset customers started calling him, and he began to have ethical qualms about selling at Silver Saddle. He’d seen too many people throw away their life savings, explained. In fact, Herrera said he’s stunned that the company can still sell the lots, and at such a high price.

“Silver Saddle is totally a rip-off,” he added.

Like many others, Herrera has let his seven plots in the second community go. He stopped paying the taxes. He advised a neighbor, who bought from the company, to do the same.

It’s not an illogical tactic. California City and Mojave School District levy parcel taxes that, together with the county’s property tax, can make holding even low-value parcels cost around $150 a year. As a result, those who hold the parcels for long periods can easily pay more in taxes than the land’s assessed value.

In fact, records show that Silver Saddle allowed 24 parcels held by itself and its subsidiary, MCQ Corp., to become tax-delinquent, and then bought them back at a 2003 tax auction.

In this year’s tax sale, 675 California City properties went to auction because of unpaid taxes. More than 600 of those were barren tracts in the second community.

Kvassay said everything his brokers do is ethical. They’re all licensed, and he touts the company’s record at the state Department of Real Estate.

His customers are well-informed, Kvassay said, and he’s got the documents to prove it.

All receive a public report on their land from the Department of Real Estate, which is often required by law. In addition, each signs a letter beginning “Dear Purchaser,” which confirms they have received and understood a variety of information. The company would not provide a “Dear Purchaser” letter for this report.

The Department of Real Estate did have at least one complaint against the company in which Wen Qian Ma alleged she was sold a piece of property for about $37,000 that had several problems with zoning, the maps and possible easement problems that she only discovered after the contract was signed. The Department of Real Estate said the case had been closed and didn’t have any further information.

Ma, a native Chinese speaker with limited English, also state in her complaint that she wasn’t given information about the property in Chinese and was not shown the public report until after all the papers were signed.

Gary Salonisen, who helped Ma with her complaint, said she was repaid all her money after three or four months of negotiations.

But Kvassay described Ma as a happy customer when he last saw her, who understood the purchase she was making. When she asked for a refund, he said the company didn’t resist.

“If she had come up and bought (property) and truly didn’t speak the language we wouldn’t have gone forward with the deal,” he said. “I sign off on those things. I’m there.”

Salonisen didn’t want to get into the details. His assessment of Silver Saddle was curt and unflattering.

“They take advantage of non-English-speaking people,” he said. “That’s their game.”

Land “Never Depreciates”

But many buyers do hang on to their land. The land Seda Shadkamyan bought was first purchased by Silver Saddle at a 2002 tax auction for $456. Silver Saddle then sold the parcel to 25-year-old Armenak Piskulyan, also of Glendale, for $17,000 in 2003.

But many buyers do hang on to their land. The land Seda Shadkamyan bought was first purchased by Silver Saddle at a 2002 tax auction for $456. Silver Saddle then sold the parcel to 25-year-old Armenak Piskulyan, also of Glendale, for $17,000 in 2003.

He stopped making payments after a car crash prevented him from working, he said. Piskulyan’s property was foreclosed on, and Silver Saddle re-sold the lot to Shadkamyan two months later, at more than double the price.

Piskulyan, meanwhile, is still making payments on two other parcels he bought from the company.

“Land never depreciates,” Piskulyan said, explaining his purchase. “That’s the basic thing everybody knows.”

After hearing the low assessed value of his parcels, Piskulyan immediately began talking about an acquaintance to whom he could resell at a hefty profit.

“The big fish eat the little fish, right?” he said, stubbing out a cigarette as his family watched television in the next room.

The Newcomers

Silver Saddle has been selling land for more than 20 years. Its predecessor company, Great Western Cities, was led by Nat Mendelsohn, the legendary Columbia sociology professor who founded California City, hoping for it to be the next Palm Springs.

But the latest land boom has brought a new, aggressive company to California City.

National Recreational Properties, Inc., a corporation that sells land throughout the country, began buying California City lots at Kern County tax auctions in 2003 and promoting them in television commercials, broadcast in Spanish and English, featuring spokesman Erik Estrada.

Like Silver Saddle, the company typically sells lots for several times what the assessor’s office considers “fair market value.” NRPI sells mainly in the city’s first community, selling lots that have water connections and are buildable, though not always with electricity or sewers.

Domingo Gomez, of Anaheim, bought two pieces of land from NRPI in 2004.

Then, on a trip to visit a few months later, he compared prices with other Realtors and was shocked. He was able to buy a $9,500 lot from Coldwell Banker that was larger and more centrally located than what he bought from NRPI for $18,000.

“The company is bad to Spanish people,” said Gomez. “We got a little money together and somebody took it.”

Gomez’s salesman was Jose Herrera, who had left Silver Saddle for NRPI. After about a year, he left NRPI because he said he had similar moral qualms about what the company was doing. He said when he was selling for NRPI, he wasn’t aware of how far above the market their prices were.

“Maybe I should have known, but I didn’t,” he said.

Herrera said company policy was to be deliberately vague about the status of a lot’s utilities, which can vary widely in the first community from block to block. After he quit, he helped several of his former clients, including Gomez, write complaint letters to NRPI asking for their money back.

Gomez reached a settlement with the company, but is forbidden from disclosing the terms.

In a written statement to this reporter, NRPI Vice President Todd Gladis said the company strived for customer satisfaction, had an “A” rating at the Better Business Bureau, and allowed any customer with doubts about a purchase to back out during a seven-day cooling off period.

The prices are fair for California City, he said.

“NRP has inspired development and brought about property value increases since locating in this unique community,” he said.

American Dream

Josue Andino, a carpenter, moved from Nicaragua to Los Angeles in 1992. He shares a small Koreatown apartment with his wife and two kids.

Andino first heard about California City from NRPI’s television ads, featuring Erik Estrada. In January, he agreed to pay $17,000 for a plot the Kern County Assessor’s office says is worth $3,000. He cursed in Spanish when a reporter told him his land had been purchased in 2001 for $450. But then he leaned back, shrugged, and sighed, like a man who felt the sting of a bad deal before.

“What can you do?” he asked. “They already sell it to me. I cannot do nothing.”

He’ll just keep working.

“First we think about them,” he added quietly, pointing to his young son, asleep under a blanket on the couch.

The price of Andino’s American dream will be steep. Under his contract, he will pay the company $291 a month for almost 12 years to get his land—a total of $43,149.